By Denis Turco

Denis is President and Managing Principal of DTA Denis Turco Architect Inc., which he founded in 1995.

Denis is President and Managing Principal of DTA Denis Turco Architect Inc., which he founded in 1995.

I was inspired to write this post by my recent "rediscovery" of an interview with Charles Eames, conducted in 1972, entitled "What is Design?".

There exists a common misconception that architects always promote formal expression, often at the expense of service. In extreme cases, critics say we are at risk of becoming "useless" to our clients, building users and to society. I believe this perspective is based on a vague, generalized understanding of what we actually do and how we work. What architects do, first and foremost, is solve problems and provide for a need. That will never be irrelevant.

There exists a common misconception that architects always promote formal expression, often at the expense of service. In extreme cases, critics say we are at risk of becoming "useless" to our clients, building users and to society. I believe this perspective is based on a vague, generalized understanding of what we actually do and how we work. What architects do, first and foremost, is solve problems and provide for a need. That will never be irrelevant.

SO WHERE IS THE DISCONNECT?

The mass media usually provides a presentation of architecture that is primarily aesthetic, often portraying the work of world-renowned “starchitects” working for clients that are more interested in achieving a visual “wow" factor than they are concerned about improving efficiency, safety or in making buildings that are a functional and sustainable place for people to live, work and visit. Sometimes this is very successful for a client or a community (For example, after the huge success of Frank Gehry's design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, critics began referring to the economic and cultural revitalization of cities through iconic, innovative architecture as the "Bilbao effect"). They talk about design theory and present the work as an esoteric, sculptural finished product. The effect of this sort of exposure has created what has often been described as the "starchitect complex". MARKETING OVER SERVICE.

Big "A" architecture, however, still needs to manage client and user requirements- all while making an artistic and, often, a discursive statement that contributes positively to our society. This isn't an easy achievement, especially if the purse-strings are held by a client on a fixed budget. Convincing a client that a formal expression is worth the expense is a talent in and of itself. Being formally expressive on a budget is an art- even if it isn't always successful. But is it even necessary? Do architects always promote formal expression at the expense of service? And what about "mundane" requirements such as programme and function? The short answer is No. Of course not.

As we certainly do in our own studio, I believe the vast majority of architects take user and client needs and requirements very seriously, and always do their best to satisfy these parameters above all else. We empathize and we listen. We are well versed in building technology, construction methods, materials, contracts, zoning parameters, building codes, engineering systems and a plethora of other things. This was clear to Vitruvius over 2,000 years ago, when he wrote De architectura. Yet, the public perception continues to often be one that sees the architect as self-serving megalomaniac that is out of touch with the needs of people. This brings me back to the disconnect...

THIS is our challenge, a "call to action" if you will: How do we, as a profession, work at repairing this misguided perception? I believe the answer lies in "process over marketing". This is what we do, and this is what we are good at.

ARCITECTURE IS, ABOVE ALL, A SERVICE WITH A PROBLEM-SOLVING PROCESS.

That we strive to create beautiful, sustainable and functional buildings should be a given. Instead, amongst everything else, we should promote the value of our service. Our client's satisfaction should be lauded; Value engineering should be praised; Contributions to the public and private realms should be celebrated. Our process should define us. SERVICE OVER MARKETING.

Big "A" architecture, however, still needs to manage client and user requirements- all while making an artistic and, often, a discursive statement that contributes positively to our society. This isn't an easy achievement, especially if the purse-strings are held by a client on a fixed budget. Convincing a client that a formal expression is worth the expense is a talent in and of itself. Being formally expressive on a budget is an art- even if it isn't always successful. But is it even necessary? Do architects always promote formal expression at the expense of service? And what about "mundane" requirements such as programme and function? The short answer is No. Of course not.

As we certainly do in our own studio, I believe the vast majority of architects take user and client needs and requirements very seriously, and always do their best to satisfy these parameters above all else. We empathize and we listen. We are well versed in building technology, construction methods, materials, contracts, zoning parameters, building codes, engineering systems and a plethora of other things. This was clear to Vitruvius over 2,000 years ago, when he wrote De architectura. Yet, the public perception continues to often be one that sees the architect as self-serving megalomaniac that is out of touch with the needs of people. This brings me back to the disconnect...

THIS is our challenge, a "call to action" if you will: How do we, as a profession, work at repairing this misguided perception? I believe the answer lies in "process over marketing". This is what we do, and this is what we are good at.

ARCITECTURE IS, ABOVE ALL, A SERVICE WITH A PROBLEM-SOLVING PROCESS.

That we strive to create beautiful, sustainable and functional buildings should be a given. Instead, amongst everything else, we should promote the value of our service. Our client's satisfaction should be lauded; Value engineering should be praised; Contributions to the public and private realms should be celebrated. Our process should define us. SERVICE OVER MARKETING.

Best known for furniture design, architect and designers Charles Eames (1907–1978) and Ray Kaiser Eames (1912-1988) got it right. They created timeless, beautiful and functional products (and buildings) with their simple process.

I was a recent architecture school graduate in the early 1990s, when I first came across the Charles Eames interview. The following excerpts are as understated as his designs, and as clear as they are brief.

Q: What is your definition of “Design”?

A: One could describe Design as a plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose.

Q: Is Design an expression of art?

A: I would rather say it’s an expression of purpose. It may, if it is good enough, later be judged as art.

Q: What are the boundaries of Design?

A: What are the boundaries of problems?

Q: Is Design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: No.

Q: Is it a method of general expression?

A: No, it is a method of action.

Q: Is Design a creation of an individual?

A: No, because to be realistic one must always recognize the influence of those that have gone before.

Q: Is there a Design ethic?

A: There are always Design constraints, and these often imply an ethic.

Q: Does Design imply the idea of products that are necessarily useful?

A: Yes, even though the use might be very subtle.

Q: Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: Who would say that pleasure is not useful?

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: The great risk here is that the analysis may be incomplete.

Q: Can the computer substitute for the Designer?

A: Probably, in some special cases, but usually the computer is an aid to the Designer.

Q: Does the creation of Design admit constraint?

A: Design depends largely on constraints.

Q: What constraints?

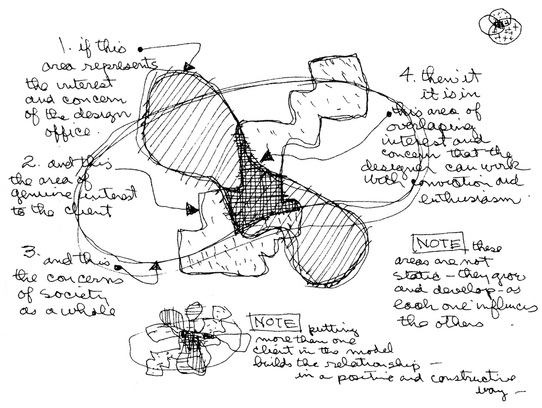

A: The sum of all constraints. Here is one of the few effective keys to the Design problem: The ability of the Designer to recognize as many of the constraints as possible. His willingness and enthusiasm for working within these constraints- constraints of price, of size, of strength, of balance, of surface, of time, and so forth. Each problem has its own peculiar list.

Q: Does Design obey laws?

A: Aren’t constraints enough?

Q: Are there tendencies and schools in Design?

A: Yes, but these are more a measure of human limitations than of ideals.

Q: Ought Design to tend towards the ephemeral or towards permanence?

A: Those needs and Designs that have a more universal quality tend toward relative permanence.

Q: To whom does Design address itself: to the greatest number? to the specialists or the enlightened amateur? to a privileged social class?

A: Design addresses itself to the need.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises?

A: I don’t remember ever being forced to accept compromises, but I have willingly accepted constraints.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of Design and for its propagation?

A: The recognition of need.

Q: What is the future of Design?

A: (No answer)

Q: What is your definition of “Design”?

A: One could describe Design as a plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose.

Q: Is Design an expression of art?

A: I would rather say it’s an expression of purpose. It may, if it is good enough, later be judged as art.

Q: What are the boundaries of Design?

A: What are the boundaries of problems?

Q: Is Design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: No.

Q: Is it a method of general expression?

A: No, it is a method of action.

Q: Is Design a creation of an individual?

A: No, because to be realistic one must always recognize the influence of those that have gone before.

Q: Is there a Design ethic?

A: There are always Design constraints, and these often imply an ethic.

Q: Does Design imply the idea of products that are necessarily useful?

A: Yes, even though the use might be very subtle.

Q: Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: Who would say that pleasure is not useful?

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: The great risk here is that the analysis may be incomplete.

Q: Can the computer substitute for the Designer?

A: Probably, in some special cases, but usually the computer is an aid to the Designer.

Q: Does the creation of Design admit constraint?

A: Design depends largely on constraints.

Q: What constraints?

A: The sum of all constraints. Here is one of the few effective keys to the Design problem: The ability of the Designer to recognize as many of the constraints as possible. His willingness and enthusiasm for working within these constraints- constraints of price, of size, of strength, of balance, of surface, of time, and so forth. Each problem has its own peculiar list.

Q: Does Design obey laws?

A: Aren’t constraints enough?

Q: Are there tendencies and schools in Design?

A: Yes, but these are more a measure of human limitations than of ideals.

Q: Ought Design to tend towards the ephemeral or towards permanence?

A: Those needs and Designs that have a more universal quality tend toward relative permanence.

Q: To whom does Design address itself: to the greatest number? to the specialists or the enlightened amateur? to a privileged social class?

A: Design addresses itself to the need.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises?

A: I don’t remember ever being forced to accept compromises, but I have willingly accepted constraints.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of Design and for its propagation?

A: The recognition of need.

Q: What is the future of Design?

A: (No answer)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed