By Sakshi Misra

Building Technologist & Designer, DTA Denis Turco Architect Inc.

Building Technologist & Designer, DTA Denis Turco Architect Inc.

As architects, we can determine the order and shape of our built environment; but equally important, or perhaps even more important, is our impact on the planet as a result of that order and shape. As our planet's natural resources are depleting, it is becoming increasingly important to consider how the needs of the future generations will be fulfilled. Sustainable design is the practice of increasing the efficiency with which the built environment consumes energy, water and materials and reducing the environment impacts of the built environment over its life cycle. One way of achieving this is by employing passive design strategies which rely on natural heating, cooling and day-lighting to reduce dependency on fossil fuels and electricity.

Sustainability and passive design strategies played a critical role in my post secondary education. From studying climatic conditions, materials, solar heating and natural ventilation, I learned the importance of extending the design beyond the walls of a building and understanding the impacts on the context. Hours of research, case studies and intense discussions informed and guided many of the design decisions for my projects. In spite of my studies, it took one single moment to fully understand the impact of successful passive design: my first visit to Taj Mahal.

Sustainability and passive design strategies played a critical role in my post secondary education. From studying climatic conditions, materials, solar heating and natural ventilation, I learned the importance of extending the design beyond the walls of a building and understanding the impacts on the context. Hours of research, case studies and intense discussions informed and guided many of the design decisions for my projects. In spite of my studies, it took one single moment to fully understand the impact of successful passive design: my first visit to Taj Mahal.

It was mid-June, the peak of summer in India. The four hour drive from Delhi to Agra had started off as cool and pleasant, but the excitement had worn off by noon as the temperature had reached 48°C. Of course, the marvel and beauty in the architecture of the ancient mausoleum was a sight to behold, but unfortunately the unbearable heat prevented me from truly appreciating it. The tour around the complex of gardens under the blazing sun had left me feeling faint. As we made our way into the main chamber of the tomb, I wished only for cold water and shade. The chamber was indeed shaded, but it was also very crowded and smelled of sweat, which made the atmosphere almost as stifling as the heat outside. Walking around the tomb near the centre, I came to a sudden stop as I experienced a cool breeze.

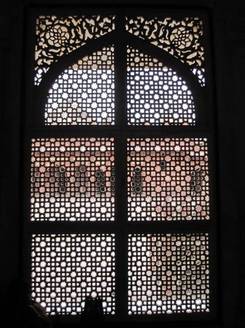

I remember looking around to find the source of the breeze, in the hopes of standing closer to the fan. My guide laughingly told me this was the beauty of the Taj; because even on a still, hot day, the interior of the chamber was kept naturally cool and ventilated. The careful placement and design of the windows created a funnel effect for the outside air. The shape of the openings, with a larger opening on the exterior and a smaller opening on the interior face of the wall, increased the air flow to fully ventilate the interior. The jali, stone latticed screens, in each opening, added to the Venturi effect by creating even smaller openings for airflow. The water channels and fountains integrated in the complex and the Yamuna River north of the Taj further cooled the air as it entered the chamber, and the double wall construction achieved thermal cooling for the interior. The sounds and smells in that chamber didn’t matter as I stood rooted to the spot, absorbing as much of the breeze as I could. A few things had become very clear to me at that point: the importance of basic human comfort; how minimal human comfort actually is; and the full impact of passive strategies.

I remember looking around to find the source of the breeze, in the hopes of standing closer to the fan. My guide laughingly told me this was the beauty of the Taj; because even on a still, hot day, the interior of the chamber was kept naturally cool and ventilated. The careful placement and design of the windows created a funnel effect for the outside air. The shape of the openings, with a larger opening on the exterior and a smaller opening on the interior face of the wall, increased the air flow to fully ventilate the interior. The jali, stone latticed screens, in each opening, added to the Venturi effect by creating even smaller openings for airflow. The water channels and fountains integrated in the complex and the Yamuna River north of the Taj further cooled the air as it entered the chamber, and the double wall construction achieved thermal cooling for the interior. The sounds and smells in that chamber didn’t matter as I stood rooted to the spot, absorbing as much of the breeze as I could. A few things had become very clear to me at that point: the importance of basic human comfort; how minimal human comfort actually is; and the full impact of passive strategies.

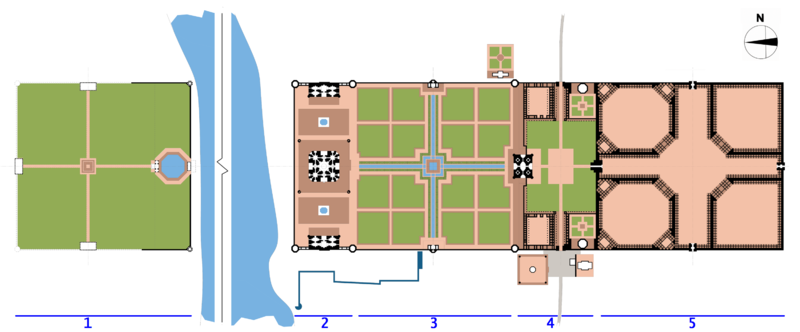

Site Diagram: 1. The Moonlight Garden to the north of the Yamuna River, 2. Terrace area (Tomb, Mosque), 3. Charbagh (The Gardens), 4. Gateway, attendant accommodations and other tombs, 5. Taj Ganji (The Bazaar).

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Taj_site_plan.png]

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Taj_site_plan.png]

Until that moment in the chamber, it really hadn't mattered that I was looking at an architectural masterpiece of the world, because my mind and body had been too overwhelmed by the heat and I was struggling to stay upright! This also led me to reflect on how it really doesn't take much to make ourselves comfortable, and perhaps we have spoiled our bodies and minds by creating such controlled environments that may be too comfortable, as we become more and more dependent on technology. We have become so accustomed to the controlled environments inside the buildings that we forget that opening or closing a window may be all that’s needed to bring sufficient comfort. This active participation and interaction between the building and the occupant is the result of passive design and creates a sense of awareness of both the interior and exterior environments. It is quite amazing to think that the Taj Mahal achieved centuries ago what we struggle with today: how our environment’s natural resources can be harnessed and used to enrich our experiences. It is proof that even as we advance in technology and innovation, it’s important to look back and learn from our past.

I find vernacular architecture, architecture indigenous to a specific time or place, quite inspiring. Tipis, igloos and mud houses are only a few examples, and all were (and still are!) successful in that time and place because they efficiently fulfilled the needs of the users with the most economical use of local materials. And it was this specificity to each physical context that created a symbiotic relationship between man, land and building. Over time, globalization has made it possible to transport any material and technology to any corner of the world, but the relationship between user, building and context has deteriorated.

I find vernacular architecture, architecture indigenous to a specific time or place, quite inspiring. Tipis, igloos and mud houses are only a few examples, and all were (and still are!) successful in that time and place because they efficiently fulfilled the needs of the users with the most economical use of local materials. And it was this specificity to each physical context that created a symbiotic relationship between man, land and building. Over time, globalization has made it possible to transport any material and technology to any corner of the world, but the relationship between user, building and context has deteriorated.

Passive strategies in Mughal architecture: Ventilation openings located high in the structure to allow hot rising air to exit as cool air enters from openings below; Jalis, stone latticed screens, used as architectural decoration and to allow for natural ventilation.

I attended a lecture recently by Rahul Mehrotra, who is a practising architect and urban planner in India, as well as a professor at Harvard University. He sees glass towers as "architecture of impatient capitalism", because many cities considered models of capitalism - like Dubai, Shanghai and Singapore - are under strict governments that can immediately prepare the ground to collect the most capital for minimum effort. This is why, he claims, towers with glass curtain cladding (being the quickest and easiest construction option), have become the symbol of "global capitalism" and an expression of modernity. Along with sustainability, social and cultural needs and values play a huge role in Mehrotra's design solutions. He gave fine examples of inappropriate use of materials and their repercussions: During some political unrest earlier this year in South India, glass buildings could be equipped with fine nets to protect them from stones thrown in case of riots. These were actual systems that hooked onto the building – and were even available in different colours, imagine that! Similarly, the climatic conditions in India are simply not ideal for tall glass towers. Although the building may be up and functioning quickly, the amount of money and effort put into the installation, operation and maintenance of blinds and air conditioning systems behind the glass is something that is often overlooked.

While explaining one of his projects in India, Mehrotra talked briefly about the interesting ways certain materials weather and develop patinas over time, and one can spend a considerable amount of time studying the effects of time and climate on these materials. He then laughed as he added that, nowadays, the discussion around the table is less about weathering and more about weatherproofing buildings.

While advancement is right, and even essential in its own place, it's also important to remember the fundamentals; like the value of a cool breeze on a hot summer day.

While explaining one of his projects in India, Mehrotra talked briefly about the interesting ways certain materials weather and develop patinas over time, and one can spend a considerable amount of time studying the effects of time and climate on these materials. He then laughed as he added that, nowadays, the discussion around the table is less about weathering and more about weatherproofing buildings.

While advancement is right, and even essential in its own place, it's also important to remember the fundamentals; like the value of a cool breeze on a hot summer day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed